By Ellaha Rasa

A woman dressed in a light blue, flower-embroidered dress stands in the center of the picture, gripping the sun in one hand and a rubab – Afghanistan’s national instrument – in the other. She gazes towards the horizon, set against a backdrop of a misty sky, flying birds, miniature clouds, and wheat branches. Tucked in the upper corner is a depiction of Helmand’s famous Bast castle.

The latest artwork from Effat Sadat Husaini, a 26-year-old Herati artist, has a defiant theme expressed through her graphic design. Central to her piece, each element of the picture embodies a brilliant past, placed on a foggy canvas to symbolize the fading glory of women, art, architecture, and music.

Husaini, a graphics graduate from Herat University, is determined to keep the glory of Afghanistan’s historical past alive through the artistry of vector graphics.

“My goal in this work is to remind people of the traditional values of those days when with the least facilities they were full of beauty. But unfortunately, today those historical works have been forgotten in addition to all today’s destruction,” she tells Rukhshana Media. She aspires to portray struggle and resistance and counter it with hope in subtle ways. For example, she uses the warm tones in the wood of the rubab’s coloring as details in miniature designs to instil hope that the unique art form of the traditional stringed instrument will endure even in the darkest of times when music is banned.

photo: submitted to Rukhshana media.

The rubab, a staple of Afghan folk music, particularly in Herat, carries an additional message in her artwork – that of breaking taboos. Before the Taliban’s ban on music and singing in August 2021, the notion of a woman playing the rubab was considered taboo in Herati society. This societal norm is precisely what Husaini seeks to challenge.

Her process begins with initial sketches on white paper. She then transitions her designs to a digital canvas using a paint box and digital brushes. Drawing inspiration from the historical monuments of the old Khorasan period, she has crafted an ancient style of art, infusing it with modern elements. This has been her focus for the past year, dedicating twelve hours a day in her workshop to study and research historical objects and the role of ancient tiles.

Her other works, Arezoo (dream) and Seven Heavens of God, follow the same ancient style and have been warmly received on Facebook. Many see Husaini’s work as a form of defiance against the Taliban’s mindset.

On Facebook, fans of the art have left comments about the impact the work has on them. Facebook user Arifa Hussainzada points to the current situation where girls are suffering from mental illnesses due to the denial of education and work. “To fight with your thoughts and hardships in life and to display your thoughts through art, and fight and create a work of art with details is itself a wonder that comes from Ms. Hussaini and comes again and again. Surely behind this artwork, there are words that we can read and interpret.”

Saif Ali Seddiqi, another Facebook user, praised her work writing, “Amid all these restrictions and conflicting thoughts, it requires a high will to create art and an artistic style.”

Born in Iran, Husaini’s family had relocated to Mashad from Afghanistan during the civil war. There were many challenges for them, including for Husaini who illegally studied up to grade five due to lack of legal residency in Iran. But when she was ten years old the family relocated again to Kabul and then Herat. Husaini made her way to Herat University’s Faculty of Fine Arts. After earning her bachelor’s degree, she worked as a guide for the “International Exhibition of Timurid Artifacts,” which kindled her interest in ancient art styles.

Following her stint at the exhibition, Husaini served as a lecturer at the Faculty of Fine Arts. But with the Taliban’s ban on women’s university education last year, Husaini lost her job. “The Taliban and their evil rule cost me a lot,” she says. “The only way I could motivate students in the field of graphics was to teach this field, but now I am deprived of teaching and my students are deprived of learning.”

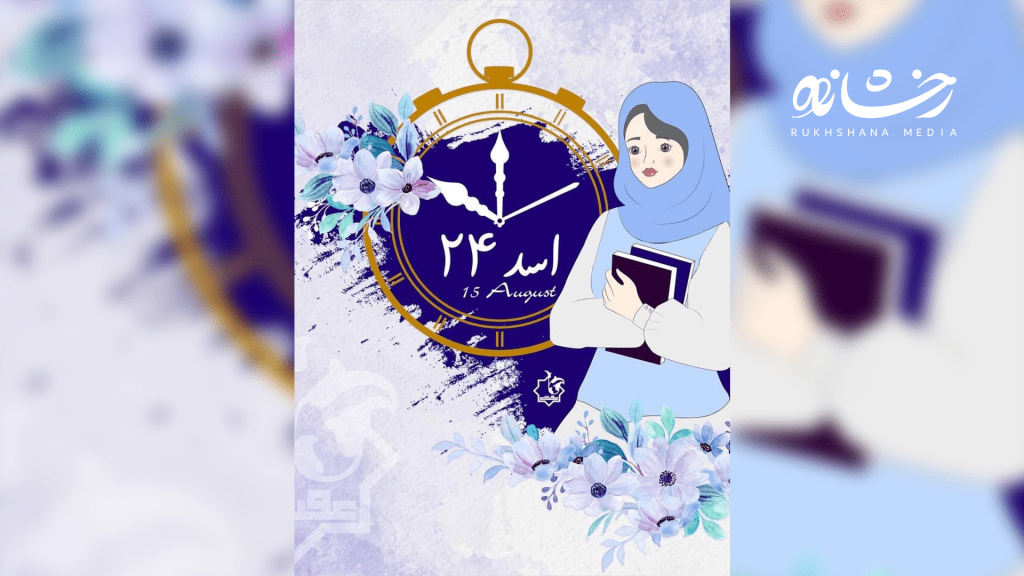

Another of Husaini’s works underscores the plight of girls in Afghanistan following the closing of schools. The piece features a girl with a clock, its hands frozen on August 15, 2021. The girl waits anxiously with her books for schools to reopen.

Explaining the artwork, she says, “Marjan was on the cusp of grade eleven at school when the dark forces of the Taliban took over her land and turned history dark once again.”

Husaini hopes that her work also serves as a galvanising force for women’s solidarity as individuals continue to defy and fight against the Taliban’s restrictions. “Each woman’s resistance creates the courage to fight in the next woman to continue on this path,” she says, hopeful that these scattered efforts will foster more shared experience.

Husaini’s graphic works are indeed rare and highly priced in Afghanistan, but often undervalued compared to their global counterparts, according to Afghan cartoonist and graphic artist, Ali Sam who is based in Germany.

Despite this, Husaini continues to present her graphic designs as both a form of struggle and a potential source of income. By publishing a series of logo designs on her Facebook page, she hopes to attract commercial companies.

“I request the businessmen to give the women a chance to prove their abilities so that more girls can work in this field,” she says. While Herati girls have been making significant progress in the field of graphics over the years, the Taliban’s restrictions have made creating art incredibly challenging for these ambitious young women.

Hussaini believes that most of them work in graphic art out of necessity of income as opposed to a love of its artistic advantages. Also it can be done online and the women don’t have to deal with the work bans from the Taliban.

“In recent years, more girls have developed good skills in the field of graphics in Herat,” she says. “I request the businessmen to give the women a chance to prove their abilities so that more girls can work in this field.”