By Mehreen Rashidi

Orzala Rahmani didn’t set out to be a painter. She was in her second year of an engineering degree when the Taliban imposed a ban on women studying at university in December 2022. She turned to painting as a way for her to channel her grief and frustration.

“In painting, I am more interested in expressing the truths and adversities of life and showing the beauty that goes through the mind of an artist. I want to relax myself through painting,” Orzala says.

Now, she also teaches others in the craft.

This month, Orzala held a painting and calligraphy exhibition with six of her students at Abida Balkhi school in northern Balkh province.

She says it was a challenge to host under Taliban rules, but they managed to bring it together. About 30 artworks were on display, most of them were conceptual themes.

“Of course, many artworks were planned to be exhibited, but unfortunately, because it was against the wishes, beliefs, and views of the current government [Taliban], we could not display them all, especially the portraits,” she says.

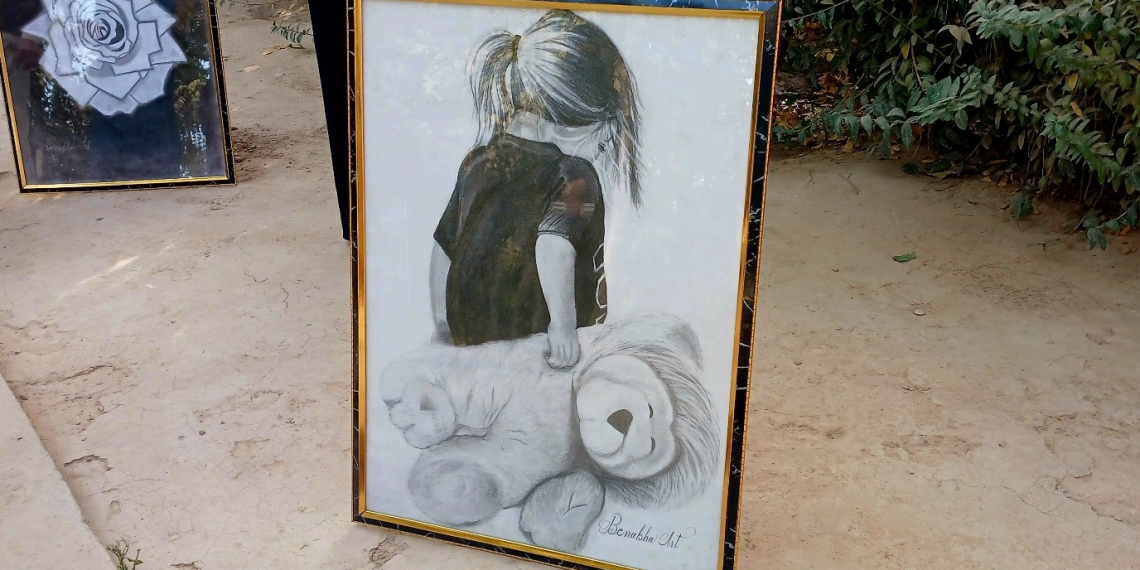

One striking painting on exhibition shows the back of a young child about four-years-old with her face turned away holding a large teddy bear behind her. Her hair is tied in a loose ponytail with her fringe and strands falling forward over her face. She is looking at the ground. It’s a forlorn scene that the artist says was her way to depict the losses in the lives of hundreds of sad and lost girls who are trapped in the fear of what to do and what not to do.

Orzala’s mother Najiba Rahmani says her daughter has been very affected by the Taliban’s ban on women studying at university. The distress and isolation of the extremist group’s 2021 return to power was compounded by the grief of Ozala’s father’s death shortly before and then Najiba’s unemployment under another Taliban decree.

Najiba, who has two bachelor’s degrees herself in literature and psychology, feels proud that her daughter has achieved so much as an amateur painter despite the isolation and emotional toll of recent years. She says Orzala’s interest in art began around nine years old.

“My son, who was in the third grade, started painting. Because I encouraged him a lot, Orzala also became interested. She was a second-grade student. She would work by herself and I would encourage her. It was in 2018 that she drew her first more formal painting and showed it to me. I posted her drawing on my Facebook. My goal was that my friends would also encourage her and she would become more interested.”

The mother’s ploy worked.

“After my friends began congratulating her, she worked harder. She didn’t go anywhere for formal training in painting. We live in Dehdadi district and the social and cultural conditions here are very bad. I also went to work from morning to evening, and Orzala, being my only daughter, had to be at home every day,” Najiba says.

Najiba says Orzala’s classes grew organically this year. She had been teaching English and Maths at an educational center, but once the students became aware of her artistic talent, they began asking for formal classes in art.

As a mother, Najiba has seen how Orzala’s talent has grown with the enforced isolation of the Taliban decrees.

“When Orzala is in a negative mood, she takes a canvas and goes to her room,” she says. “When she gets better, she takes her painting and shows it to me so I can see how it turned out.”

“Because my daughter has seen a lot of pain at this age, she paints such sad paintings. It has been two and a half years since she lost her father. Her father had cancer. I used to be the head of women’s affairs in Dehdadi [government sub-branch of Balkh women’s affairs department], but became unemployed when the Taliban regained power. Later, I found a job in an NGO, but I was unemployed again due to the Taliban banning women from working in NGOs.”

Fear keeps some people away from the exhibition

The exhibition was held outdoors at Orzala’s former high school Abida Balkhi in Dehdadi district. The organizers say for it to be open to the public, they had to follow very strict Taliban conditions.

Most of those who attended the November 4 event were girls and women, all wearing the same flowing black hijabs with black veils and masks.

Despite adhering to the conditions, fear of any perceived threat from the Taliban meant many stayed away. One man, who requested not to be named, left quickly after he arrived at the exhibition area.

“When I entered the gate, I saw all the girls and women wearing black,” he says. “Honestly, I was shocked. I stood there and did not dare to move forward. I hesitated and asked one of the girls if I could see the paintings. She said I could. I went a little further and saw one or two paintings, but I could not go further because on both sides there were girls standing in black from head to toe and no man should be seen between them. So I left urgently.”

Each of the 30 painting is evocative and poses questions.

In one of the paintings, a person is clawing at a giant wall clock before them, while reaching up with their left hand to pull the second hand of the clock backwards.

In another painting, a girl is inside an hourglass, sitting forward with her head cradled in her hands. The sands of the hourglass are falling on her shoulders.

A third dark painting shows a wolf howling in the night, a faint light outlining its coat and just penetrating the tree leaves around it. Behind the wolf is the shadow of a woman with the distinct outline of a black hijab wrapped around her. The wolf’s head is thrown back in a howl towards the sky. The steam from its mouth shows the cold air in the grove.

A fourth stark painting is an abstract man with an oversized heart bigger than his body tied on back. He is leaning forward with the weight of it, walking on a path through a desolate landscape. The trees in the scene have what looks like brains growing on them instead of leaves.

Orzala says because girls are banned from an education above grade six, most of them only ever show people at home their work or hang them on the walls at home. The exhibition was a chance to communicate their art with others.

She says the exhibition is also a way of protesting the current situation in Afghanistan where girls and woman have no voice, and a way of encouraging new artists to emerge.